Blog 1: Urban green spaces

What is an accessible urban green space?

As we begin the Bristol Quiet Areas Plan 2025, we aim to understand what makes green and blue spaces genuinely accessible, comfortable and restorative for neurodivergent people – and, ultimately, for all of us. The project is being co-created with Disability Inc (WECIL), Visit West, and neurodivergent adults whose lived experience guides the work.

What is an urban green space?

Above: Temple Church Gardens, Bristol

An urban green space is any publicly accessible area in a city where nature is present – trees, planting, water, shade, or quieter places to pause. This includes parks, pocket parks, riversides, churchyards, planted streets, community gardens, courtyards, meadows, and small nature-filled corners.

Inclusive design guidance highlights that these spaces must be:

- Easy to reach

- Simple to understand and navigate

- Comfortable – physically and sensorially

- Flexible, supporting different ways to use them

- Predictable and safe, reducing cognitive and sensory load

Urban green spaces are essential infrastructure: they support wellbeing, reduce pollution, cool the city and enhance biodiversity. Britain has around 62,000 urban green spaces*, yet access varies. Bristol ranks highly for total green space (3rd in the UK in 2023)**, but the Ordnance Survey found that only 6.76% is publicly accessible, showing a clear gap between provision and usable access.

Crucially, size is not what makes a space valuable. A small, shaded, quiet spot can be deeply restorative when it is welcoming and easy to reach.

* UK natural capital: ecosystem accounts for urban areas.

**National #GetOutsideDay 2023

What ‘accessible’ really means

Accessibility goes beyond ramps and gradients. True accessibility is whether someone can reach, understand, use and feel comfortable in a space without unnecessary stress.

Throughout life, we all experience changes in mobility, sensory processing, energy levels, anxiety or confidence. The Equality Act, BS8300, PAS 6463 and Building Regulations recognise this as universal.

From a lived-experience perspective, accessibility is about:

- Ease – getting there without barriers

- Clarity – intuitive layouts and predictable routes

- Comfort – environments that don’t demand coping strategies

- Choice – the freedom to pause, retreat or connect

WECIL emphasises that accessibility must support emotional and sensory needs as well as physical ones.

Distance as access: 200m and 50m

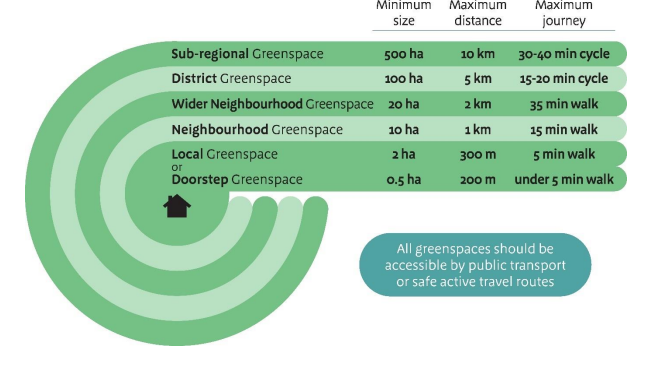

Proximity is a significant part of accessibility:

- Natural England recommends green space within 200m of home.

- Active Travel England advises resting places every 50m.

- BS8300* recommends frequent rest points with footpath gradients no steeper than 1:21.

At some point in our lives, all of us will experience mobility challenges – temporary, fluctuating or permanent. For many people, including neurodivergent adults, disabled individuals, older residents and those experiencing fatigue or pain, distances beyond 50m become significantly harder without somewhere to pause.

For some, 50m is the threshold that determines whether they can participate in city life or must stay home.

This is why inclusive mobility guidance and Blue Badge standards emphasise shorter, more manageable distances: if a space is not reachable, it is not accessible.

*BS 8300-1:2018 Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment – Part 1: External environment – Code of practice

Conclusion: Green spaces need to be everywhere

Image: © MawsonKerr Architects, Joint winner of Home of 2030+

For cities to be genuinely inclusive, green and blue spaces cannot be occasional destinations –they must be everywhere, part of everyday movement. Long distances and unpredictable environments exclude many people.

The 50m principle helps us rethink cities as networks of small, accessible, nature-rich places people can easily reach to pause, regulate, orient themselves or continue their journey.

These points do not need to be large or formal: a shaded bench, a planted corner, a quieter waterside edge, or a small pocket of vegetation can provide meaningful support when they are nearby and welcoming.

An inclusive city is one where green spaces are embedded throughout daily routes, and where people can move without being pushed beyond their physical or sensory limits every 50m.

; ?>)